No messing about this time, just solid top-tier Dredd all the way. How can anything be better than...

Epic 16: Oz Progs 545-570

Written by John Wagner & Alan Grant; Illustrated by... deep breath... Brendan McCarthy; Will Simpson; Cliff Robinson; Steve Dillon; John Higgins; Barry Kitson; Jim Baikie; Garry Leach; Dave Elliot

(26 episodes, 199 pages, epic 9 in sequence)

The Basics: Skysurfing champ Chopper escapes from prison and surfs all the way to Oz to compete in Supersurf 10. Meanwhile, Dredd investigates a plot against the city by a rogue cult of Judges, coincidentally also based in Oz.

|

| Part escape/survival story, part action/espionage romp, part sports. This part's the sports. Art by Jim Baikie |

Analysis: A story very much of two parts, tenuously linked, this is a stone-cold classic. It's also barely a Judge Dredd story. It's a Chopper story, with a Dredd mini-epic chucked in the middle. Both parts are so good, though! The Dredd bit covers the secret existence of the Judda. These are the servants of Morton Judd, one of the founding Judges, one who pushes the fascist dictatorship angle of the Judge system to an extreme. Perhaps coincidentally, perhaps not, this comes up exactly at the time when Dredd is tackling the rise of democracy in Mega City 1. We the readers, and Joe Dredd the Judge, both have a chance to really think about what Mega City One is actually like, for good and ill. It's cracking stuff, and without it, we wouldn't have had either Necropolis or America.

Well, maybe we would, but Oz acting as a prologue makes both even better!

So it's a little sad that the Judda really only take up 6 episodes of Oz. On the other hand, those episodes are drawn by Brendan McCarthy at the absolute peak of his powers, and a young Will Simpson who came into his own as a superlative Dredd artist in this very epic, getting even better with his painted work in the build-up to Necropolis.

|

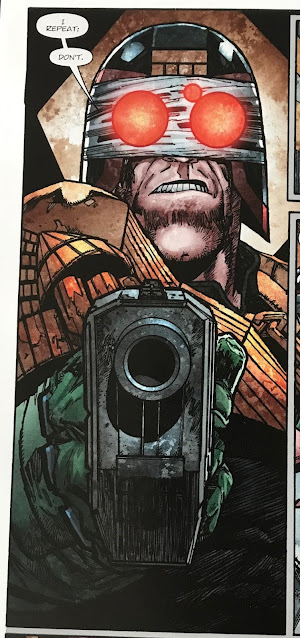

| Bad craziness afoot in Mega City One Art by Brendan McCarthy |

The real hero of Oz, though, is Chopper the skysurfer. His voyage across the Cursed Earth and then the Pacific is just long enough and weird enough that you really feel the miles. Then there's the fairly straightforward recounting of Supersurf 10, which to retell doesn't seem like much, but is in fact a masterclass from Wagner and Grant in how to write sports comics. Just enough character so you care about the competitors. Exactly the right number of twists and turns. And gory deaths.

|

| Chopper begins his impossibnle journey Art by Garry Leach / Will Simpson (I think?) |

|

| Sports comics at their pinnacle of excellence Art by Barry Kitson |

And of course the notorious double-ending, which gives Chopper a taste of both failure and victory. You can see why Wagner and Grant disagreed about how to finish up this tale. Grant's preferred ending, that Dredd executes Chopper (perhaps after letting him win the race?) makes logical sense, given Dredd's character and history. Wagner's preferred ending – the one we got, where Chopper loses the race, but Dredd lets him escape (that's how I read it, anyway), makes emotional sense. You can't follow Chopper across 26 episodes of tragedy, triumph and tragedy again, only to kill him off. You just can't! And then of course Wagner gives Chopper an even greater follow-up story a year later, in Song of the Surfer. Dredd's decision, too, surely feeds into the ongoing subplot of his increasing doubts about the justice system.

|

| Chopper's defining characteristic - anti-authoritarianism Art by John Higgins |

Story: 9/10 (Wagner and Grant)

Art: 7-9/10 (Everyone)

If there's one thing that lets it all down, it's the fact

that this epic needed a bajillion artists. There's a new team on the job every

single episode for the first 8 in a row (although some were artists

working under pseudonyms, a fair disguise for rushed team-effort work). Some of them

returned later for a section each of the surfing competition. The greats get to

make their mark, certainly: Cliff Robinson opens it up with a spectacular

prison break, and at the other end Jim Baikie really nails the emotions of the

ending. And there's nothing bad about any of it. But it makes for a jarring

read. The one note of consistency comes from Brendan McCarthy, who suggested

the setting and some of the basic plot ideas in the first place. His Judda

sequences sure were memorable and creepy. Kind of sad that he didn't get to deliver and skysurfing sports action, though.

Legacy: From the Judda part of the epic, we got Kraken

– not named here, but he's going to be a BIG deal coming up. Morton Judd, too,

rears his head again in Origins. There's also Oz Judge Bruce, who'll come a

cropper next time we see him. Chopper was already a star, but this story got

him promoted to his own series, complete with supporting cast. The best of these, Jug McKenzie, even gets to appear in a Dredd tale without needing Chopper there as well.

Overall score: 17.8 out of 20

Want to read it? Good! It's excellent. I'm kind of hoping that one day there'll be a reprint that includes the colour pages, (I even bought the Hachette version hoping for that but no dice). For now the easiest way to get the whole thing is Case Files 11.

Next up, the epic that revitalised not just Judge Dredd, but arguably gave 2000AD itself a shot in the arm that kept it going into the new millennium...

Epic 15: The Pit Progs 970-999

Written by John Wagner; Art by Carlos Ezquerra, Alex Ronald, Colin McNeil, Lee Sullivan

(29 episodes, 191 pages, Epic 19 in sequence)

The basics: Judge Dredd is sent into a run-down region in the NorthWest Hab Zone to root out corruption in a Justice Dept Sector House, and to reduce crime rates across the entire Sector.

|

| Dredd's always at his Dredd-est when shown alongside other characters. The Pit has the best side-characters. Art by Carlos Ezquerra |

Analysis: Now this was an epic for the ages, and the first modern epic to really tackle a key part of Judge Dredd: he’s a police officer, which means offices, administration, and lots of colleagues. The set-up is simple, Dredd is sent in the clean up a run-down Sector House, rooting out local corruption and fighting off a local crime lord. Yes, the much earlier 'Graveyard Shift' had tackled a similar theme of Judges just getting on with it, but that was more about the crime, while 'The Pit' is much more about the job, and the effect it has on those who do it.

To some extent, the clean up / anti-corruption storyline is

so good, that the finale with the war against crimelord Fonzo Bongo was a bit

of a let down, not helped by the rotating art team. King Carlos delivers a

glorious cast of all-new characters; Messers MacNeil, Ronald and Sullivan do

their best to follow in his footsteps but it's just not the same when Carlos

isn't on duty. Possibly this was a clever metaphor for the reality of a police

station requiring shifts, and inevitably one shift is stronger than another. Or

possibly not.

|

| Out on patrol with other Judges from the Pit Art by Alex Ronald |

But that's the negative out of the way! Pretty much everything about this storyline was from the very top drawer, with Wagner doing some fine character work alongside his classical crime story plotting. So many characters are introduced, get their own mini-arcs and go through their own stages of growth and change, even (to an extent) Dredd himself, who hates desk work and organisation, but learns to respect that it must be done, and done well. There's even an element of mystery for us readers to enjoy. After introducing nearly a dozen major players, we, along with Dredd, have to learn who is a rotten apple, and who is, in fact, an honest Judge – albeit with a few vices. Wagner knows how to plot this kind of thing out, giving you some obvious villains, some red herrings, and some with just plain surprising back-stories.

To help out with this angle, Wagner brings in an older but

generally successful epic trope: a hand-picked team of old

favourites to help Dredd out. In this case it's Judges Giant and Castillo, who

help the setting feel that much more lived-in. In another world, Wagner

could’ve made this story run and run, perhaps with a rotating cast of

characters as new washed-up Judges are sent to the Pit to shape up, kind of

like a TV police drama. Instead, he has to wrap things up, and while ending on

a siege is dramatic and thrilling, the villain of the piece never quite earns

his place as a capable threat, and certainly his threats are less exciting than

the early part of the story’s concerns about who may or may not be corrupt.

|

| A powerful send-off Art by Lee Sullivan |

Story: 10/10 (Wagner)

Art: 6-10/10

Ezquerra does everyone proud in his usual making-it-look-easy

way. In particular, it’s the cast of characters. Each and every one is

recognisable and has personalities that come through in the art, even though

they’re all judges with identical uniforms. His Dredd particularly impresses,

though, shown here not in a constant flurry of action but sometimes sitting

behind a desk, or just talking to people. He never loses his imposing

character. And of course Ezquerra knows how to deliver action/thriller beats as

the story demands. A young Alex Ronald gets to shine in a sequence or two that

rely on emotion and inner turmoil. MacNeil keeps things noir-ish, and Lee

Sullivan puts in creditable work on the cartoonier end. But all three suffer

somewhat under the glowing colours of Alan Craddock. He has his strengths, but

it’s a jarring shift from Ezquerra.

Legacy: Well, there's quite the bunch of new recurring

characters to talk about, starting with Galen DeMarco, who would go on to

appear in several subsequent epics, before graduating to her own solo series.

But there's also brutish but loyal Judge Buell, wayward and tough-as-nails

Judge Guthrie, and also the seeds of a hidden villain, known at this stage only

as the 'Frendz'.

From a more high-level perspective, we get a bit more of a sense of the day-to-day workings of the Judges, but also the very premise of telling a longer story from the perspective of a group of Judges, a theme Wagner will return to again and again.

Overall Score: 17.9 out of 20

Want to read it? Best to get the collected edition, otherwise this epic falls in an awkward way meaning it was stretched over two Case Files, 24 and 25.

It's not all classic thrills at this top end of the ranking. Here's an epic from recent times that really hits the spot...

Epic 14: The Small House Progs 2100-2109

Written by Rob Williams; Art by Henry Flint

(10 episodes,

62 pages; epic 49 in sequence)

The Basics: Judge Smiley, who helped Dredd defeat the baddies during the Trifecta epic, is exposed as a baddie himself. Dredd and a select team of trusted Judges want to bring him to justice – but a traitor lurks among them.

|

| When a superior asks you in for 'a word', you know it's bad news. Art by Henry Flint |

Analysis: This epic is the culmination of a far bit of Rob Williams’ work on Dredd, going back to the Low Life story ‘Creation’, via Trifecta, Titan/Enceladus, and one specific prologue to this epic, ‘Act of Grud’. In that story, Judge Sam manages to uncover that something in Justice Dept is using alien tech to create the ultimate stealth warriors, who are assassinating people following some secret agenda. We also see that Dredd has gathered a small team of trusted colleagues to help root out this corrupt Judge dept. The Small House is all about that team finally getting to the bottom of things and putting an end to it - but probably it’s always going to be more famous as ‘that one story where a Judge explicitly talks about being a fascist’.

That said, this isn’t an epic about fascism or the Justice system’s approach to power. Rather, it’s a very high stakes techno action thriller. It has a clever and intricate plot, based around several characters who are all trying to keep up with each other, and a villain who is mostly interested in playing chess with humans. The kind of villain it’s REALLY fun to outwit, and boy does this story boast a killer ending on that front (albeit an ending that doesn’t entirely make sense, if you think about it too hard).

|

| The Small House: the one with Sam, Frank and the big red quantum goggles. Art by Henry Flint |

I suppose the thematic weight of the story is about Dredd, who is genuinely all about upholding justice and protecting the citizens, versus Smiley, who seems to be more concerned with holding onto power and only protecting citizens in order for him/the Department to have a body of people to have power over. So where Dredd is a character concerned with writing instant wrongs, now, Smiley is all about the long term and the bigger picture, prepared to sacrifice a large number if he believes it will secure a better future for a fractionally larger number. And he does like to go on about Dredd being a tool rather than a big thinker, which rubs both him and us up the wrong way; double fun to see him get his comeuppance at the end!

So what about that line where Smiley says, ‘we’re fascists’? I’m not convinced he’s using the word correctly. Dispassionate authoritarians, sure, but fascists? Of course, it’s one of those words that has developed ameaning over time that has evolved from its roots in 1920s Italy, and it’s not really the place to debate semantics in the pages of an action thriller. The point being made is that Smiley thinks his actions are obviously for the good, at least, if you buy into the idea of Justice Dept as a force for good. Arguably, he’s even right. But inarguably, he’s the bad guy in a story who obviously thinks he’s doing something dodgy otherwise why hide from the Chief Judge? Why not assume she’d actively encourage his decisions? I wish Williams had given a bit more room to explore that, because there’s an undercurrent of this specific story that is all about Smiley thinking he’s better than Chief Judge Hershey, and also Dredd thinking HE’s better than Hershey, too – as he refuses to clue her on on what he’s up to. Hershey really does get shafted in this story, and it’s not a coincidence; Williams is leaning into it in the same way he had been throughout Titan/Enceladus.

So yes, while the political questions underlying the story are ignored, what Williams (and indeed Henry Flint) does real well is the character interplay. There’s Smiley himself, who loves lording it over everybody, but more so there’s stone-cold Dredd, who refuses to share much with even his trusted teammates: Giant, Maitland, Gerhard, Sam and Dirty Frank. And this irritates them all. In an epilogue of sorts, Pets, poor Giant is left marvelling at just how much Dredd does not care about other people’s feelings, or even pay any mind to what those feelings might be, or how they could influence a plan’s chances of success.

And then there are some pretty shocking plot twists / betrayals that power through the back half of the epic, bringing on another round of extreme emotions in both characters and readers (or me, at least).

In all, it’s a satisfying thriller that touches upon something weighty themes – but then falls short of unpicking those very themes. I mean, in the span of a 6-page episode I’m not sure there was another way, but I am sad that other characters weren’t given the chance to ponder – was Smiley in the right?

|

| Would you test this man? Art by Henry Flint |

Story: 8/10

Art: 10/10

Legacy: More of an end-point rather than a

legacy-generator, this story. It is arguably the final nail in the coffin for

Hershey, who very soon quits as Chief Judge. It’s also the end of the line for

Dirty Frank (in the world of Judge Dredd, at least…), and perhaps for now puts

an end to stories about ‘what if there was an evil and sinister group of judges

that even the judges don’t know about’. (Although in the Michael Carroll

universe we do still, I think, have an ongoing plotline about an evil sinister

group of gangsters who have managed to plant various moles in Justice Dept).

Overall Score: 18 out of 20

Want to read it? Here's a handy collection.

Next time, back to the old school, and four epics that if I'm honest, are my favourites, even if they haven't scored out as 'best'. Like all such things, they're not scared to show their imperfections.

Just a quick note to say that Oz appeared in 1988, when all the media in the world (including Inspector Morse and The Archers) went to Australia for the bicentennial.

ReplyDeleteOOh I'd quite forgotten that! It's a good point.

DeleteI read Dredd not keeping Hershey in the loop in Small House as being the same reason he didn't in Trifecta- she's being listened in on (by Bachmann's psi in Trifecta and Smiley in Small House). A small group of street judges can meet covertly but once you involve the chief judge, it's a lot harder to keep things private. That's the big theme of Small House for me- private action vs. public action. Dredd enforces the law in plain sight, Smiley does it covertly. That, and tying up some dangling storylines.

ReplyDeletePublic action vs private action - an excellent observation. I think there's quite a long history of Justice Dept hiding things from Dredd because they know he'd object and raise an almighty fuss.

ReplyDeleteYou name check Bachmann in the small house. Did you mean Maitland?

ReplyDeleteI certainly did! Fixed it now, many thanks. Honestly, as a glasses-wearer myself, you'd think I'd be less quick to mix up glasses-wearing judges. Presumably, in a world of bionic eyeballs, this is an affectation on a par with growing moustaches...

Deletegood grief, that Brendan McCarthy you picked is a beaut. He is such a master at the little add ons to the Judges' regular uniforms, in this case a monocle of all things

ReplyDelete